The Psychology of Saving Money

To begin the new year, I began coursework towards my CFP designation. My goal is to increase my knowledge of technical aspects of financial planning where I lack formal education or expertise in order to better serve this audience.

At the same time, I started reading Morgan Housel’s book The Psychology of Money. In it, Housel focuses exclusively on why we do what we do with our money. Sometimes, those actions may appear insane to others.

This all has me thinking about how to help you do better with your money. What is the relative importance of the technical aspects (what to do and how to do it) in personal finance? What role do psychological aspects (understanding why we do things and using that knowledge to promote better behaviors) play? Where should we focus our attention?

As I explore new topics with increased technical depth, it’s important that I don’t drift too far from my roots in the FIRE community. Despite lacking technical expertise, we’ve managed to achieve financial outcomes that are rare in our society.

Nowhere in this FIRE community do we get things more right, both tactically and psychologically, than with saving money. So it’s worth exploring exactly what we do differently than most. Why do we do those things? What we can learn from it?

Is Saving Money Hard?

I frequently share my story on general personal finance platforms as an example of what is possible. We achieved financial independence (defined as having accumulated greater than 25 times our annual spending in invested assets) decades earlier than most people. We accomplished this primarily by saving roughly half of our household income for about 15 years.

When I share that fact, I nearly always get some version of the same question as a response. Isn’t that hard?

The question is understandable. But it misses a key point.

It assumes that the standard path must be easy, since it is what most people do. That assumption is dead wrong!

We’re often told we should try to save about 10% of our income. Standard advice is to have an emergency fund of three to six months worth of expenses. So understandably, saving at five times that rate and accumulating decades of living expenses sounds difficult to achieve.

But the fact is that the standard path is hard. Many people listen to standard advice and struggle with their finances. A recent survey found that only 44% of Americans could pay for a $1,000 emergency from their savings.

Vanguard’s How America Saves 2021 report showed that the median retirement account balance for those ages 55-65 is only $84,714. Assuming a 4% safe withdrawal rate, that means they can spend only about $3,400/year to supplement any Social Security benefits at the start of retirement.

So let’s take a closer look at the psychology and tactics of saving 50% of our income vs. saving 10% of our income and reconsider our assumptions.

The Scenario

To show the impact of a 10% vs. a 50% savings rate, we will use this example. Let’s assume a household has a monthly income of $10,000*. They are starting with no savings or debt on January 1, 2022. They will put all they save into a savings account and not invest until their emergency fund is fully funded with 3-6 months of expenses.

(*Note: I chose these assumptions because they make the math easy. I’m aware that for some of you reading this that seems like an unachievable high income number. Others may make multiples of this and still don’t think you could possibly save 50%. This is all part of the psychology of saving. I’m going to ask you to suspend your preconceived notions and follow the example through.)

To start, we’re going to ignore taxes, inflation, investment returns, pay raises, etc. I realize this is not how the real world works, but factoring in all of these variables unnecessarily complicates the scenario while detracting from the main take home points.

The Math of Savings Rates

Consider what happens when we follow standard advice and save 10% of our income. We start with $10,000, spend $9,000, and save $1,000. At the end of January, we have 1/9 ($1,000/$9,000) of one month’s expenses saved.

This continues each month we continue to save 10%. So at the end of February we would have 2/9 of a single month’s expenses. We would have 3/9 of one month’s expenses at the end of March and so on.

If we save 50% of our income each month, we will save $5,000. That is five times as much as the household saving 10%. So at the end of January, we will have saved $5,000. This is simple and intuitive.

What is less obvious is that we have lowered the bar on how much we need to save to support our spending. Instead of spending $9,000/month, to save 50% we’re now only spending $5,000/month. The $5,000 we saved in January represents one full month’s expenses.

This continues each month we save 50%. So at the end of February we have saved two months of expenses, at the end of March three months of expenses, and so on.

The Psychology of a High Savings Rate

What many people miss when they ask if saving 50% is hard is the impact of momentum. Success begets more success.

Saving for an Emergency Fund

Let’s follow this example until we amass a fully funded emergency fund of 3-6 months expenses.

Saving 10% of income, it would take 27 months (2 years, 3 months) to save 3 months of expenses. Saving 6 months expenses would take 54 months (four and a half years). If you start building your emergency fund in January 2022, you would reach your goal of saving three to six months’ expenses sometime between March 2024 and June 2026.

In contrast, if you are saving 50% of your income, you would have saved an emergency fund of 3-6 months expenses in 3-6 months. You would reach your goal between March and June of the year you started.

Yes, you have to save five times as much. But you achieve your savings goal in 1/9th the time.

Once you achieve your goal, you immediately experience the benefits of a fully funded emergency fund. They include the ability to:

- Pay for a large unforeseen expense without going into debt

- Cover living expenses for several months if you lose a job

- Direct future savings to investments that will start compounding.

Feelings of achievement, momentum, and security can and will propel you forward.

If saving only 10%, progress will be painfully slow. When it takes several years to build the emergency fund, there is also an increased likelihood that you’ll actually have an emergency in that longer period of time.

It is easy to get off track or quit trying altogether. It’s not surprising that statistics show the average American has so little saved.

Saving for Retirement

Play this scenario out to retirement. The exact same principles apply. The amount you will need to support you in retirement is dependent on how much it costs to support the lifestyle you want to live.

Let’s assume you can withdraw between 3-5% of your invested assets to support retirement spending. The inverse of this means you would need between twenty to thirty-three times your annual expenses at the start of retirement.

If you spend $9,000/month, or $108,000/year, then you would need to accumulate between $2.16 million and $3.56 million. Saving only 10% or $1,000/month, that would require either unexpectedly high investment returns or more years of compounding than you likely have available.

If you spend $5,000/month, or $60,000/year, you would need to accumulate between $1.2 million and $1.98 million. Saving 50% of your income and investing at conservative return assumptions, it is reasonable to assume you will achieve financial independence in less than twenty years.

Is it easy? No. But in my humble opinion, it’s a whole lot easier than never achieving financial independence.

The alternative is relying on a paycheck into your 70’s and government programs in retirement. That’s not easy either. Yet few people try to achieve financial independence because progress is so slow and the goal so far in the future when following standard advice.

That psychological reframe is powerful for many people. The upside of understanding the psychology of saving is that it can inspire action.

Regardless of how much motivation you have to save, we need to understand what actions to take that will actually move the needle.

The Math of Increasing Your Savings Rate

First, you have to understand what savings rate is:

Savings Rate = Savings/Income

Stated another way:

Savings Rate = (Income-Spending)/Income

Returning to our example household saving 10% of income:

Savings Rate = ($10,000-$9,000)/$10,000 = $1,000/$10,000 = 10%

There are two clear actions you can take to increase your savings rate. You can increase your income, keeping spending constant. You can decrease spending, keeping income constant. (A third option is to work on both components simultaneously.)

If you had to choose only one, it is faster and easier to increase your savings rate by decreasing spending. There are mathematical and tax reasons that make this true.

Using our example, decreasing spending by $4,000/month looks like this:

Savings Rate = ($10,000-$5,000)/$10,000 = $5,000/$10,000 = 50%

Using our example, increasing income by $4,000 looks like this:

Savings Rate = ($14,000-$9,000)/$14,000 = $5,000/$14,000 = 36%

In either case, we increased our net savings by $4,000 and improved our savings rate. But when we decrease what our lifestyle costs, we simultaneously lower the bar for how much we need to save.

The math clearly shows that if your goal is to increase your savings rate, spending less is more impactful than earning more, all things equal. But all things are not equal.

Tax Advantages of Spending Less

To this point, we’ve ignored taxes so as to keep the example simple. But in the real world taxes exist and they provide extra incentive to be more frugal.

Assume our example household is in the 22% marginal tax bracket. If they want to increase their income by $4,000/month, they would have to actually earn an extra $5,685 after accounting for federal income and payroll taxes. This doesn’t account for any state or local taxes they may also owe.

If they wanted to cut spending by $4,000, they would have to spend exactly $4,000 less.

This tax advantage alone is powerful if you’re looking to direct savings to debt payoff or building an emergency fund quickly. As you can start directing savings into tax advantaged investments, you can further decrease your tax burden and accelerate reaching financial goals.

Related: Early Retirement Tax Planning 101

The Tactics of Increasing Your High Savings Rate

We now understand the psychology and math of savings, but we still need to understand the tactics. Once again, standard personal finance advice is failing most people.

There are endless articles about the “latte factor” and cutting the cord. An entire reality series was dedicated to extreme couponing. News stories frequently shame the poor for buying lottery tickets or owning fancy cell phones.

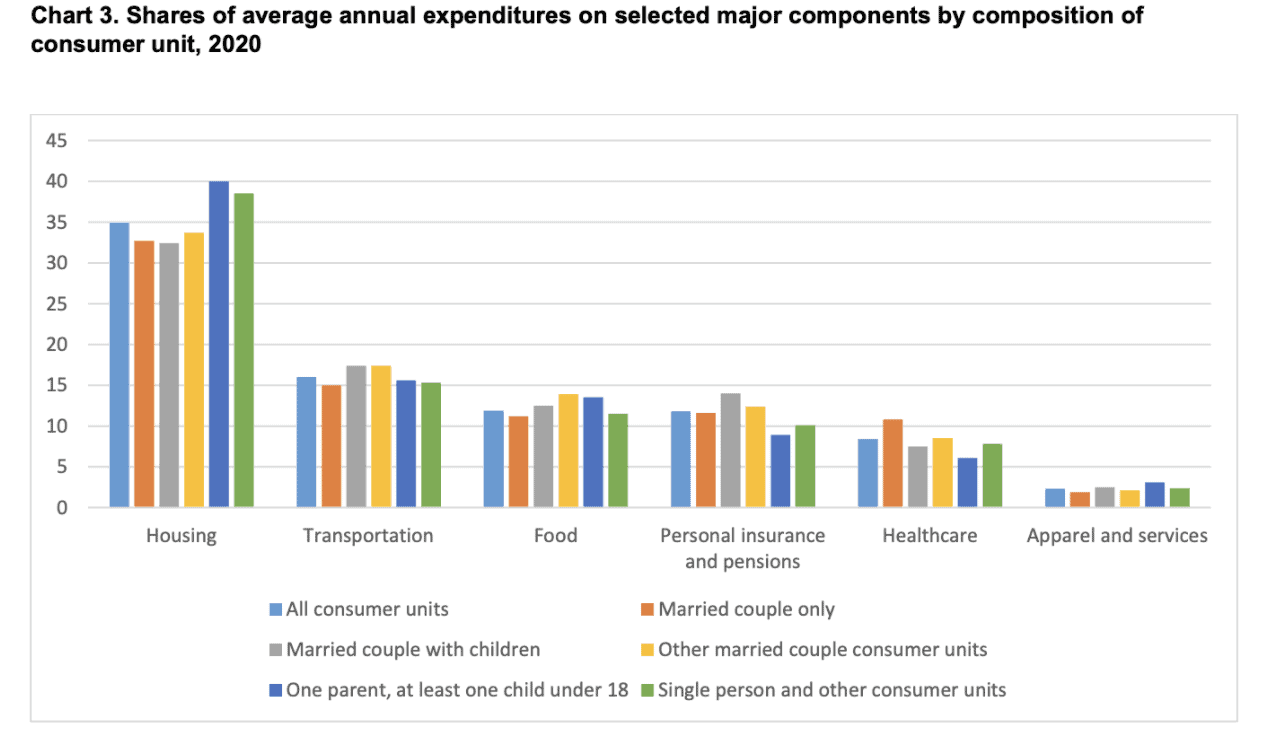

Check out this chart from the Department of Labor’s 2020 Consumer Expenditures Report.

Combined spending on housing and transportation represents at least 50% of average household spending across all demographic groups. Food accounts for at least another 10%. That’s over sixty percent of most household’s spending.

Focus on optimizing spending on housing, transportation, and food first. Systematize and automate your finances so your money is going where you want it to go every month without applying effort or even thinking about it and you are on the path to a high savings rate.

Taxes are not accounted for in the consumer expenditure report, but they are a large expense that can be lessened with good planning. Once you have adequate savings and liquidity, you can start considering self-insuring.

Reassess taxes and insurance needs once a year, automate actions, and forget about them for another year. These actions accelerate an already high savings rate with zero sacrifice (unless you enjoy paying taxes or insurance premiums).

The alternative is to buy into the narrative that saving requires sacrifice. Ignore the big ticket items and instead focus on lattes, lottery tickets, and your cable bill.

That advice is great for getting clicks to a website or starting arguments on social media. But it really doesn’t move the needle if we actually want to develop a high savings rate that can change your future.

The Psychology of Financial Independence

In The Psychology of Money, Housel has some great quotes about the importance of financial independence.

“Being able to wake up one morning and change what you’re doing, on your own terms, whenever you’re ready, seems like the grandmother of all financial goals.”

“The ability to do what you want, when you want, with who you want, for as long as you want to, pays the highest dividend that exists in finance.”

Housel is a fabulous writer. He wrote an excellent book packed with valuable lessons and timeless knowledge.

In one of the last lines in the book, he writes of his family’s approach to money, “We think it’s the ultimate goal; the mastery of the psychology of money.”

I ultimately disagree with his final conclusion. Mastering your money is a mix of mastering psychology and knowing what actions to take to actually move the needle. We need both.

* * *

Valuable Resources

- The Best Retirement Calculators can help you perform detailed retirement simulations including modeling withdrawal strategies, federal and state income taxes, healthcare expenses, and more. Can I Retire Yet? partners with two of the best.

- Free Travel or Cash Back with credit card rewards and sign up bonuses.

- Monitor Your Investment Portfolio

- Sign up for a free Personal Capital account to gain access to track your asset allocation, investment performance, individual account balances, net worth, cash flow, and investment expenses.

- Our Books

* * *

[Chris Mamula used principles of traditional retirement planning, combined with creative lifestyle design, to retire from a career as a physical therapist at age 41. After poor experiences with the financial industry early in his professional life, he educated himself on investing and tax planning. Now he draws on his experience to write about wealth building, DIY investing, financial planning, early retirement, and lifestyle design at Can I Retire Yet? Chris has been featured on MarketWatch, Morningstar, U.S. News & World Report, and Business Insider. He is also the primary author of the book Choose FI: Your Blueprint to Financial Independence. You can reach him at chris@caniretireyet.com.]

* * *

Disclosure: Can I Retire Yet? has partnered with CardRatings for our coverage of credit card products. Can I Retire Yet? and CardRatings may receive a commission from card issuers. Other links on this site, like the Amazon, NewRetirement, Pralana, and Personal Capital links are also affiliate links. As an affiliate we earn from qualifying purchases. If you click on one of these links and buy from the affiliated company, then we receive some compensation. The income helps to keep this blog going. Affiliate links do not increase your cost, and we only use them for products or services that we’re familiar with and that we feel may deliver value to you. By contrast, we have limited control over most of the display ads on this site. Though we do attempt to block objectionable content. Buyer beware.

Join more than 18,000 subscribers.

Get free regular updates from “Can I Retire Yet?” on saving, investing, retiring, and retirement income. New articles weekly.

You’re Almost Done – Activate Your Subscription! You’ve just been sent an email that contains a confirmation link. Please click the link in that email to finish your subscription.

Editor’s Note: It’s been a while since we’ve mentioned Chief Income Strategist Marc Lichtenfeld’s core investing system, the 10-11-12…

Copyright © 2024 Retiring & Happy. All rights reserved.